From Mudras to Myths: The inner grammar of Indian dance

Whether it is dance or music or any other pursuit, is it not primarily about one’s sensibility, sensitivity, and education—what in India we call our sanskara?

George Arundale, a theosophist and disciple of Annie Besant, said: ‘We educate the mind, after a fashion, at the expense of the physical body, which is bad enough, but far worse is our almost total neglect of the feelings, desires, the emotions—of infinitely greater importance these than the mind, though equal in importance to the physical body. We acknowledge the science of mathematics, of chemistry, of physics, of geology, of astronomy. We acknowledge the sciences of geography, of literature, of history, of music, of painting, of craftsmanship. But in the comparatively unevolved state of education there is no place for the science of emotions so rightly stressed in ancient Indian education. This science is a field in itself, and all we have to show for it is a psychology which avoids all that is of vital importance in the constitution of the individual life we are supposed to be educating.’

The fact that our education and now, alas, our arts are for performance, for competition, the fact that they exalt the mind at the expense of all other states of consciousness, stimulating pride in superiority, leads to a grinding demand for unrighteous pre-eminence by the performer, the competitor. These cravings represent a lower aspect of human feeling as compared to one’s aspirations, that represent a higher aspect. What may be called the ‘body of emotions’ is at the core of our being, upon which the intellectual mind and the physical body depend.

Our education in general, and in the arts especially, is essentially about courage and enthusiasm—courage to face life’s difficulties, troubles, and frustrations serenely, strongly, cheerfully. And an enthusiasm for the truth, reverence for knowledge systems, understanding the other, compassion and appreciation.

The arts have advanced these values by tapping into our aesthetic and imaginative capacities. As we adapt this objective to the Indian context, a number of philosophical, political, and practical questions come into play, ranging from those of equity of access to arts education for the underprivileged, to ways in which arts education can shape the cultural imagery of a just and equitable society. What are the ways in which the language of art can enable the voicing of alternate experiences, aspirations, and identities that lie outside socially accepted norms?

The value of art for all children cannot be underestimated. Art reflects an interest in the varied expressions of life and nature. The varied expressions of nature, the feelings of people, the nature of discord, and the love for the universe; but also, the unnatural in nature, the inexplicable, that which cannot be understood, that which requires contemplation and reflection—this is the preoccupation of art. You cannot separate art from life, the micro from the macro.

From the very start, in all Indian dance forms, especially the classical, seemingly micro-positions of the fingers called hasta mudras coordinate with positions of the head, accompanied by neck and eye movements—which together like a symphony aid and abet the macro movements of the body as a whole. These are considered ‘graces’ without which the whole has no meaning, almost. It is what happens between two beats that is the magic of dance.

It is akin to placing an object in a room. Where you choose to place it, what angle you place it in, what lies next to it, and what the background to the object is—all these matter. On the other hand, it is arguable that the object can be placed anywhere and it will find its own space.

It is the privilege of the dancer in India to gradually grow into a consciousness of these and of the many other arts and intellectual processes that inform the dance. It never fails to amaze, how varied these other arts are and how their particular fragrance enhances the art of dance. So much so, that without their presence the dance is simply incomplete. These arts were meant to be expressed together, as a single and whole offering. This does not take away from their individual merit or distinction to stand on their own.

You cannot be a sound Bharata Natyam dancer, for instance, if Indian philosophy, customs, or ritual practices evade you. Certainly, your knowledge of Indian mythology has to be thorough, if not an obsession. India’s temple architecture, sculpture, iconography; textiles, and jewellery; its languages, especially the ancient ones like Tamizh, Sanskrit, and Telugu—their prose, poetry, and recitation, vocal and instrumental music—the language of rhythm; a knowledge of the six seasons in nature and the their unmistakable connect to our five senses, physiology, anatomy, yogic practice, reeti-rivaaz or customary practice both past and present; as also sampradaya or propriety—where every nation or society has a different notion of these. The list of these interdependent knowledge systems is truly endless for a dancer. But most important, and perhaps least talked about, is philosophy.

You only have to look at our myths and Puranas to know how complicated our concept of the truth is, as also the lush fertility of our imagination! In the epics of India, at first glance incidents seem like yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Actually, in time–space it could be a lifetime, an avatar or a yuga even, that separates these incidents. This is ‘us’. We do not conform to linear time. Our lives are punctuated by events that are cyclical in nature. In relation to the infinite cycle of time and the mythological concept of time, human existence pales into insignificance. An adept dancer with a sound knowledge of the Puranas, for instance, as seen in senior Kathakali dancers, may well be arguing with his enemy on stage, but relates to the audience a similar incident in the past when the gods and demons fought over a similar matter. This can be boastful in nature, or hilarious even in that he puts paid to the remarks of his illustrious opponent. Moving between mythological space and the present is totally natural for him and the audience gets it.

This, of course, is an actor–dancer’s delight! Such an amazing wealth of narrative and audiences who understand them too! In such a scenario, what does the actor who presumably reflects or comments upon this complex society do? In theatre, they do the story as it is written, or do a ‘take’ on it—which is either hilarious, or pathetic, or blasphemous, or bold, or different. In music, they feed the story nostalgia and have a raga tell it like no narrator can. They give it rise and fall, pathos and bhakti or devotion. In films, they throw in songs that enhance the mood of the moment, they have a comedian funny it up, a villain pepper it up, a gangster blaze it up, a moll sugar it up and, of course, the most ‘beauteous’ belle of them all—kickstart the whole thing up! I love all these forms of art. But I believe the ploy used in the classical dance forms of this country to be the most unique. In the classical solo traditions, it is nayika, the woman who tells her story. She is a metaphor for male, female, and others. She is the jiva atma, the human soul.

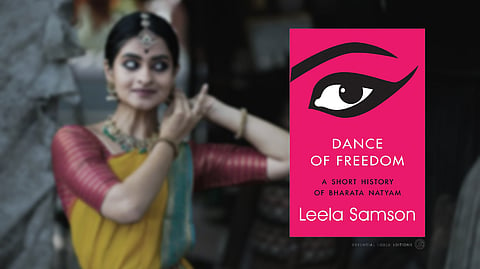

(Excerpted with permission from Leela Samson’s The Dance of Freedom; published by Aleph Book Company)

.png)